Accel

Why Accel Invested in Facebook, Scale AI, and Flipkart, and why they passed on Cisco, Skype, and Flickr.

After discussing two venture firms, a16z and Initialized Capital, both founded in the last 15 years, we’re going way back to 1983, the founding year of Accel.

Accel has been an early investor in massive companies like Atlassian, Slack, Etsy, Discord, and Dropbox, among many others. Its portfolio also includes the three companies we’ll discuss today: Facebook, Scale AI, and Flipkart.

Though there have been bumps in the road on their journey, as with any firm that has been around for 40 years, Accel has always been at the forefront of innovation, investing in technologies and trends before many others see it.

Today, we’ll learn why Accel invested in Facebook as the only VC firm the founders ever considered, why Accel invested in Scale AI before the AI movement was flourishing as it is today, and despite the founding CEO being 19 years old, and lastly why Accel invested in Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce company that was operating in a minuscule technology market in 2008 when Accel invested.

As we investigate why Accel invested in these three companies, we will analyze the firm’s general investment thesis, what they look for in founders, what traits make good VCs, and some general advice they have for founders.

At the end, we’ll examine some multi-billion-dollar mistakes Accel has made in their storied career, including one they won’t be too upset about for reasons you’ll see later.

Let’s jump in.

Why did Accel Invest in Facebook?

Any story about Facebook’s fundraising journey is always entertaining, and how Accel invested in Facebook is no exception. Like many other VC firms, Accel struggled in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble. They were having trouble adjusting to the new wave of the internet and figuring out which companies would be everlasting, and which were just a fad.

In the pre-2000s era of venture, companies were founded by seasoned industry veterans moving slowly and surely. In the dot-com bubble, however, the founder archetype changed to fresh-eyed founders hacking their way into a company and worrying about everything else later.

The era of “move fast and break things” had begun, and Accel was a little too cautious.

As we’ll talk about more later, Accel missed companies like Skype and Flickr primarily due to concerns with the legality of the endeavors and the youth and recklessness of the founders. They didn’t realize this was becoming the new normal in the startup world, and they’d have to adjust.

Missing these deals made the Accel team realize they had to reassess their strategy and start looking at the new wave of internet companies defined by social networks. In 2004, Accel began looking at social network companies. They looked closely at blossoming names like Friendster and Myspace but thought it was a little too much of a free-for-all based on all of the prostitution and illegal activity that was occurring on the lawless website.

This time, they made the right choice to pass.

However, Accel kept looking, and one partner, Kevin Elfusy, discovered a small website called “Thefacebook” through a part-time Accel scout enrolled at Harvard.

No wonder so many VC firms hire scouts with strong networks. Accel made multiple billions of dollars because of this part-time scout. Insane.

While Accel passed due to MySpace’s and Friendster’s disorder, they were fascinated by Facebook’s night-club-like strategy of slowly onboarding networks of prestigious college universities to make it a constantly high-value product.

The problem is, as we covered in the Sequoia essay, Mark Zuckerberg and Sean Parker did NOT like VCs and wanted nothing to do with them.

Accel tried everything they could to get a meeting with Facebook, primarily using LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman, a Facebook board member, to try to get in contact with the Facebook team but never found success. The Accel team was constantly told that no VC would pay enough for what Facebook was worth.

Eventually, they met with Matt Cohler, one of the first employees at Facebook and a former partner at Benchmark. Accel learned about the never-before-seen growth and retention numbers that Facebook was having. They were in awe of the company and eventually convinced the team that they would be offered a term sheet at a compelling valuation if they came to the Accel offices for a meeting.

So, I’m very much glossing over why Accel invested in Facebook because, as I just hinted at, it was obvious. Every VC wanted to invest in Facebook. There was no product in the world at the time that users loved more and every user wanted to have. They were masterfully rolling out the product campus-by-campus at a rate that mastered retention and immediate growth when expanding. It was remarkable.

What’s interesting about this story is that Accel was the only VC firm to actually get the Facebook team even to consider a deal from a venture capital firm, let alone accept one.

Before Accel met with the Facebook team, Sequoia partners Doug Leone and Mike Moritz warned Accel about the founders’ insulting conduct and that taking a meeting wouldn’t even be worth it.

Those who have read the Sequoia essay can understand why.

However, the Accel team didn’t care because they could see that the VC industry was becoming a founder-led industry. No more would the venture capitalists dictate the terms. Exceptional internet companies with incredible profitability potential were starting, and as Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google showed the following generation, founders captured the leverage in the relationship.

For exceptional founders and companies, VCs need them more than they need VCs, and Accel recognized this. To secure this deal with Facebook, they understood that the founder was the smartest person in the room, and they made sure that Zuckerberg knew they felt that way. Founding partner of Accel, Arthur Patterson, has a great quote on this concept of recognizing and emphasizing the fact that the founder is the smartest person in the room. He once said,

“To have a successful career in venture capital, you've got to be somebody that figures out who the smartest guy in the room is on any particular deal as opposed to thinking you're the smartest guy. The problem a lot of really brilliant people in the business have had over time is they're used to being the smartest guy in the room, and they're used to making those decisions, and they don't have the objective of finding somebody smarter than they are.”

I’m not saying Sequoia lost the deal because they thought they were smarter than Zuckerberg. That deal was doomed from the start. What I am saying is that many other VCs in this era still thought they had control. They thought founders without operating experience couldn’t scale companies without the venture capitalist, so the founders would come crawling to them.

But as we said, that era was becoming extinct.

Accel had a very cards-on-the-table approach. They knew Facebook was special, and they wanted to invest. They had to sell their services, and sucking up, for lack of a better word, was the correct strategy to intrigue the anti-VC Facebook team.

Funny enough, Facebook had an offer from The Washington Post for $10m at a $60m valuation. I can’t begin to explain how insane things would’ve been had The Washington Post owned about 17% of Facebook. Maybe by IPO they would’ve been diluted down to say, conservatively, 5%. That 5% in 2013 would’ve been worth about $3,000,000,000. What’s so crazy is that in 2013, Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post for $250,000,000! 12x less than what their Facebook ownership would’ve been worth! Just an outrageous story. I can’t believe the Washington Post almost led Facebook’s Series A.

Facebook almost went with the Washington Post because they assured Zuckerberg that they would be a check and there if he needed them, but if not, The Washington Post would let the Facebook team do whatever they wanted, once again appealing to the anti-VC team.

To counter this, Accel offered $10m at an $80m valuation, allowing Facebook to retain about 4.5% more of the company, which, at IPO, was worth about $4.5b, so that’s a lot of value the Accel team was willing to sacrifice to land this deal.

It was still a hard decision for the Facebook team and one that reportedly had Zuckerberg on the floor of a restaurant bathroom sobbing over due to the stress of the situation. Mind you, Zuckerberg was 20 years old at this time in 2005. 20!

The final nail in the coffin in landing this deal was Mark’s respect for Accel’s former partner, Jim Breyer. He liked Breyer’s calmness and confidence in challenging situations, and Zuckerberg knew Breyer had an exceptional track record of guiding startups to success, traits that co-founding partner Arthur Patterson considers vital to being a good VC. He once said,

“The entrepreneur should understand his industry and market in a vertical way better than anybody else, but the venture guys should bring horizontal best practices views to that individual and help that individual.

I would say you try to get them to do what's in their own self-interest, but it has to be their idea. The most effective venture guys are the guys that are able to form really close relationships with the entrepreneur and help that guy avoid a lot of mistakes and reinforce naturally good analytical judgment and get him to move a little bit faster.”

So, to win this deal, Accel made clear to Zuckerberg and the Facebook team that they were in charge, had the leverage, and that the Accel team would be there simply to help avoid mistakes and reinforce good judgment when needed. They expertly teetered on this line to essentially do what many VCs do now: support when needed, but otherwise, stay out of the way.

Zuckerberg felt that Jim Breyer and the Accel team would give him that type of partnership, so Accel (through luck, skill, luck, intense pursuit, luck, and whatever God they thanked) led Facebook’s Series A round and invested $10m for 12.5% of the company.

Eventually, Facebook would explode into the public markets at a $104,000,000,000 valuation, making it by far the largest IPO at the time, until usurped by Alibaba’s outrageous $231b IPO valuation.

At IPO, Accel owned 11.4% of the company, likely investing somewhere between $30-60m total after many large rounds Facebook raised later on. Assuming $45m of total capital invested, Accel 266x’d their capital for an ownership position at the IPO worth roughly $12,000,000,000.

So, investors, sometimes, to achieve one of the greatest investments of all time, you have to exude confidence, experience, and good judgment, but most of all, just let the founder run his or her company on their terms and make that very clear at the inception of the partnership.

Why did Accel Invest in Scale AI?

From one 19-year-old founder to another, this is the story of why Accel invested in Scale AI.

For those who don’t know, Scale AI essentially helps companies build, train, and utilize their own AI systems by providing the infrastructure and services needed to develop a model. It’s my understanding that Scale AI is like AWS for AI, but forgive me for oversimplifying if I am.

As I suggested, Scale AI was co-founded by 21-year-old Lucy Guo and 19-year-old CEO Alexandr Wang.

Hilariously young.

Accel partner Daniel Levine first heard of scale after Justin Kan, founder and CEO of Twitch, accidentally published Scale AI on Product Hunt while the Scale AI team was going through Y Combinator.

As funny as it may sound, in 2017, Daniel Levine of the premier VC firm Accel cold emailed this 19-year-old founder asking if they could meet to discuss the company.

Another reminder that venture capital is all about hustling your way into a deal before anyone else, no matter how prestigious your firm is.

Levine quickly realized there was very little data to go off of to analyze the viability of this investment, so once again, as with most early-stage investments, he had to consider this investment based on the strength of the founders.

It didn’t take long for Levine to realize this was an exceptional team, with Guo dropping out of CMU (Pittsburgh!) and leading an engineering team at Quora and Snapchat, again, at 21 years old, and Wang, born at Los Alamos, yes Oppenheimer Los Alamos, to parents who were top physicists in the country. Wang would go on to win several national programming competitions and lead an engineering team at Quora, again at 19 years old.

Soooo, yeah... Definitely smart people here.

When writing about why Accel invested in Scale AI, Daniel Levine mentioned that Scale was at the intersection of two themes the Accel team loves to back: Productized AI and APX. He describes APX as follows:

“Our APX thesis is that more and more business processes will be abstracted into APIs so that developers can easily integrate them directly into their applications, accelerating productivity. AI, like software, will have an enormous effect on productivity. It is still early days for AI, but we believe companies will be able to deliver better products powered by AI. Customers shouldn’t necessarily need to know there is AI at work, just that their experience has been magically improved. Scale hits both points with their simple API and the use of AI in the background to continually improve the value to customers.”

This sentence, Customers shouldn’t necessarily need to know there is AI at work, just that their experience has been magically improved, is essentially Scale AI’s value prop.

So, reading that in 2024, it’s easy to be like, yeah, obviously, that’s a valuable business for companies. However, in 2017, when Accel invested, it was unclear how many businesses would need the capabilities that Scale AI was offering. Sure, many companies were using AI, and Scale AI did see some fairly quick success, but mind you, Nvidia, the picks and shovels business for all AI-focused companies, has gone up about 500% in the last 18 months, so it really was not that obvious until very recently.

However, Accel has had a long-standing thesis regarding the digitization of every industry, so as Levine described earlier, Scale fit well in their thesis, even as mainstream AI development was in its somewhat early stages.

Current Accel partner Amit Kumar described this thesis as follows:

“It's sort of an inevitability at this point that the true digital transformation of every industry is taking place. One of the factors why there's so much capital flooding in the markets is that there are actually so many great companies to be built right now in all of these verticals, and I think that software eats the world is really taking place.

The potential of AI and machine learning and what it can accomplish, I think we're not even scratching the surface. I think that it's really going to be transformative for a bunch of different categories in terms of driving efficiencies that were not possible before but also driving huge societal changes in terms of employment and jobs in particular sectors. I think we're close to a revolution there.”

Well, we’re currently in that revolution. It’s impossible to read any tech news story and not hear something about AI, and every investor, startup, and large enterprise is trying to leverage AI as much as they possibly can. The digitization of every industry by utilizing AI is in full effect, and Accel was ahead of the curve in 2017 when they invested $4.5m in Scale AI’s Series A after sending that wonderful cold email to a teenager.

Since Scale AI is still a private company, I don’t have exact numbers, but since this was a Series A investment, It’s safe to assume Accel took a 20% ownership in the company, as standard with Series A investments. They have invested in the Series B and C, either maintaining or increasing their ownership, but for the sake of this discussion, we’ll assume Accel has invested $30,000,000 into Scale and currently holds their 20% ownership stake. As of May 2023, Scale AI was valued at $7,300,000,000, so Accel’s position was worth roughly $1,500,000,000.

I’m sure they’re very excited about that eventual IPO of a company that will surely be worth more in the coming years. A huge winner in Accel only came from believing in the excellence of founders before they could even have their first drink and by having strong conviction around a thesis that AI will empower all businesses to improve their processes and digitize their workflow.

Why Did Accel Invest in Flipkart?

For those who don’t know, Flipkart is the largest e-commerce site in India. They command 48% of the e-commerce market compared to Amazon’s 26% share, and in 2023, they grossed about $23 billion in sales in a ballooning e-commerce market in the most populous country in the world.

But in 2009, Flipkart was a couple of guys in their apartment packing and shipping books themselves (sound familiar?).

Many people today are bullish on India. It’s nearly a consensus opinion that there are many technology companies to start in India, and as the country continues to be pulled rapidly out of poverty and into an internet-run world, companies will flourish.

In 2005, however, India was an afterthought. China was beginning to blossom, and most VCs were starting to look there for the opportunities we are now seeing in India. But Accel wouldn’t be Accel without being contrarian, insightful, and ahead of the curve of massive technological innovations. The story of why Accel invested in Flipkart begins with this long-standing thesis of Accel, though recently re-articulated by partner Sara Ittelson, where she said,

“A lot of innovation happens maybe in pockets where people aren't looking. When you think about a lot of the founders that we talked to, it's not that they got working on this project in the last 12 months. It's that they started in 2017 or 2018, and this has been a long love, passion and exploration of the cutting edge of the technology. It's just now come to the forefront.

But I think an observation was just, great innovation is happening in little pockets where people aren't looking, things that are outside of the flow of conversation, they'll become apparent 5, 7, 10 years from now and be really life-changing for all of us as consumers, as operators within enterprises.”

As I said, Accel was essentially on their own in India in 2005. Very few VCs were operating in India, certainly a pocket where people weren’t looking.

Since they were so early, it took some time to get their feet off the ground, as common with the venture capital industry, but all of that changed in 2008 when the Accel team met the Flipkart founders Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal.

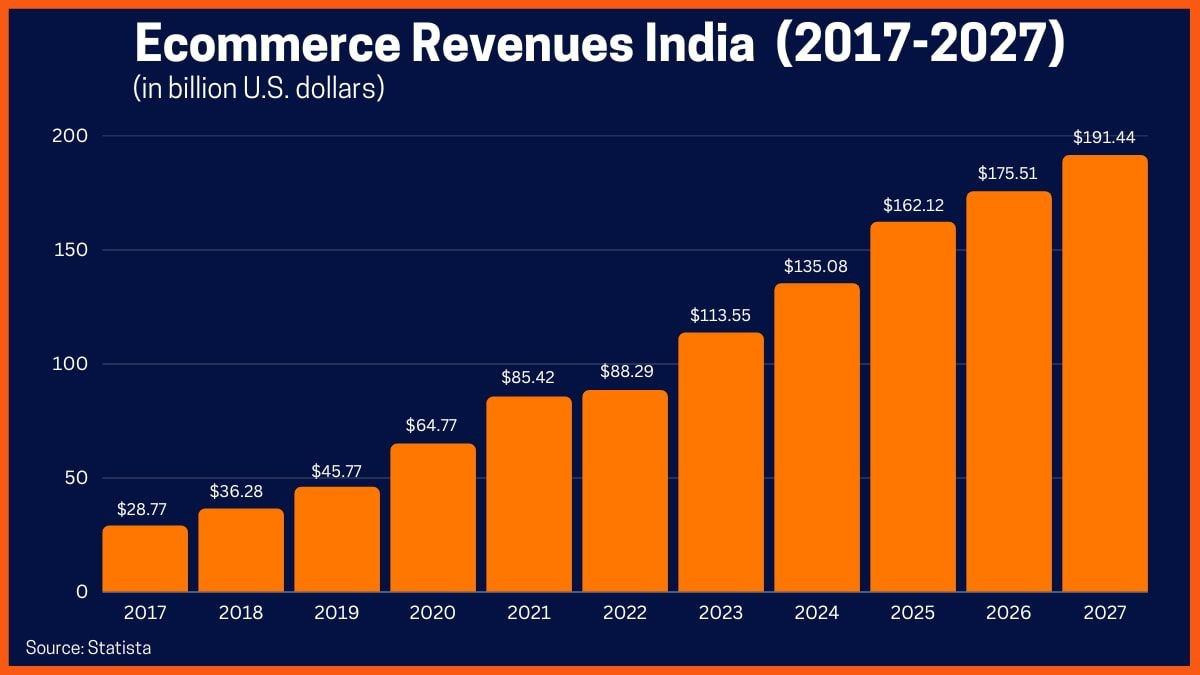

I almost think it’s redundant to put in this chart since it doesn’t start until 2017, but based on this insane growth rate, it’s safe to assume that the entire e-commerce market in 2008 in India was probably around $5 billion.

NOT a large market.

But the Flipkart founders were just so scrappy and driven to capture the Indian e-commerce market, which they knew had massive potential.

Accel partner Sameer Gandhi described his initial impression when visiting the founders' office/apartment as follows,

“In those early days, Sachin and Binny worked out of a makeshift office as they put together the beginnings of one of India’s first eCommerce businesses. One room was their warehouse, the second housed the tech team, and the third was customer support. One thing that still sticks with us is how they promised to usher in a revolutionary customer-first approach to their business, which, even though Flipkart has scaled thousands of times since, remains one of the core principles of the company even today.”

Having the founding principle of excellent customer service and starting with selling books, I mean they had to have modeled their business off of Amazon. Obviously not a bad move, but even so, India in 2008 was a vastly different world than America in 1996. It was Somewhat similar in minimal internet adoption, but different worlds of consumerism in general. It was not obvious that the e-commerce market in India would grow to a large market, let alone Flipkart be the company to lead the charge.

There was so much uncertainty that Accel was the only investor to give Flipkart an offer. Many VC firms passed, including Sequoia, which passed multiple times.

Side note: It always amazes me how every investor can pass on a startup except one firm, especially when that firm is Accel, which is exceptional in its own right. You’d think that if a founder was struggling to raise money, they’d eventually raise from a lesser-known fund, but no Accel led this round. The best investors are non-consensus and right and Accel was as non-consensus as possible, being the only investor, and as we’ll see later right to the tune of billions of dollars in returns.

So, yes, Accel believed in the founders. They were exceptionally focused and supremely driven by delivering the best experience possible for the customer, two fantastic traits to have in a founding team. However, this was just as much a bet on India as it was on Flipkart. After all, this was an investment in the Indian e-commerce market, or else Flipkart would never scale.

Well, Accel clearly believed in India, or else they wouldn’t have opened an office in Bangalore. Accel partner Mahendran Balachandran once described the founding thesis of Accel’s India office as follows. He said,

“I think for India, the theme has always been one big theme: It’s these zillions of opportunities for you to dramatically increase your productivity cycles across all industries. That has been a very common theme whether you’re in e-commerce, mobility, or food delivery.

Systematically go look at every element of it. You’re just basically removing a lot of inefficiencies in the whole system… Across the whole of India, across all spectrums of consumption, across all the ways you educate yourself in the whole everything… It'll permeate across the board because there's so much of an inefficient system. You just take them all out one after another.”

As we touched on with Scale AI, Accel believes in finding technologies to unlock production. India has a lot of pent-up production. They’ve historically been a very smart and hardworking country, and as internet adoption continues, the country and its people will flourish.

Since Accel embraced searching for opportunities to unlock production in pockets of the world no one was looking by investing in India, and by trusting the founding team of Flipkart to lead the charge based on their scrappiness and focus on their customers, Accel led an $800,000 seed round in Flipkart in 2008.

As with any company trying to build their own distribution network, Flipkart raised billions of dollars, with Accel reportedly investing somewhere around $100,000,000 total into the company to amass a 7-10% ownership by the time Walmart bought a 77% ownership stake in the Flipkart, valuing them at $20,000,000,000, and Accel’s ownership at around $1,500,000,000 - $2,000,000,000. A 15-20x on a lot of capital invested, and a 1,875-2,500x on that tiny non-consensus $800,000 seed check in Flipkart that catalyzed the India tech movement as a whole.

In this case, Accel was non-consensus and right to a degree I don’t think I’ve covered before in this blog.

Anti-Portfolio:

So, it should be clear to you by now that Accel is one of the best venture capital firms in history. I mean $12 billion from Facebook, about $4 billion combined in Scale AI and Flipkart, and probably over $10 billion combined in companies like Slack, Atlassian, Dropbox, and Qualtrics, I mean just an exceptional track record with well over $25 billion in returns.

Unreal.

Although, no firm is impervious to the mistakes that will be made in a multi-decade VC firm. So as always, we’re going to look into a few mistakes Accel has made on their way to the top.

Why did Accel Pass on Investing in Cisco?

I know nothing specifically about why Accel passed on Cisco, only that they did. What I also know, however, is all of the red flags Cisco had when Sequoia remarkably led their Series A in 1987.

First, for those who don’t know, Cisco had created the first router to connect to a network without having to physically be attached to that network so that the two founders, a husband and wife, could communicate with one another from different departments where they taught at Stanford. Essentially, they constructed a bridge over two different networks, giving Cisco the very simple summary of their business: “We network networks.”

Customers loved the product. Sequoia founder Don Valentine described HP as “tearing the hinges off the doors to get the products.”

So, you may think a revolutionary technology and ecstatic customers would make a sure-fire investment. Well, there were a few factors keeping this from being as simple as it sounds.

The first issue was that Black Monday (a day in which the Dow Jones lost 23% of its value) happened just a few months prior, and VC funding was retracting. Less money at play means higher conviction investments are required.

Unfortunately, this is where the second issue comes in, as the founders, Leonard and Sandy, gave many investors pause. Leonard supposedly was a genius engineer but a horrible communicator who struggled to say any sentence an average person could understand. He was highly technical and could not turn it off. Sandy, on the other hand, was loud, abrasive, and confrontational. Many investors were concerned that these two would struggle leading teams of employees and decided they’d save themselves from the future headache of dealing with the two eccentric founders.

So, again, I have no factual evidence as to why Accel passed on Cisco, but I’d assume it was the market conditions and the founder profiles.

So why did Sequoia invest? Well, Don, having worked with difficult founders of the past with the likes of Nolan Bushnell of Atari and Steve Jobs of Apple, knew he could work with difficult and unique founders. He was willing to deal with a few headaches to invest in a revolutionary product its customers love.

I know I often talk about how important the founder is to an early-stage investment. After all, we just discussed how a major investment thesis of Initialized Capital is to invest in founders and companies you’d want to work for.

Apparently, working with these founders felt like hell, but at a certain point, when product feedback is as positive as it was for Cisco, you need to just bet on the product to drive the company, and the rest will get figured out.

Investing in founders you don’t fully trust is scary, but investing in such an innovative product is necessary.

Why did Accel Pass on Investing in Skype?

Missing Skype was kind of a sacrifice to land Facebook. At least, I’m sure that’s how the Accel team likes to think about it.

It was 2003, and Accel was pretty lost after the dot-com crash. They had only invested in four software companies that year, a number far lower than average, primarily due to them missing the birth of social networking.

Skype was certainly a revolutionary social product on the internet. It slashed the cost of long-distance calls, pricing itself severely lower than competing services. Customers loved Skype, but the founders of Skype were not the typical clear-cut founders of the old internet that Accel was accustomed to backing.

The Skype founders previously had been sued by the entertainment industry over online music theft and were very aggressive and non-responsive in the term sheet negotiation. Once again, as we saw with Facebook, the entrepreneurs were dictating the terms.

This is a very similar story to Accel’s investment in Facebook, which would happen about a year later, only this time, for Skype, the founders' personality and lack of control the investors felt caused them to pass here.

Like I said, luckily, they learned from their mistakes when they invested in Facebook.

Skype certainly would’ve been a 100x investment for Accel, potentially returning billions of dollars had they done this deal, as Microsoft bought Skype in 2011 for $8.5b.

BIG miss driven by the old world of venture capital where the investors dictated the terms and founders came in clean-cut packages.

Why did Accel Pass on Investing in Flickr?

So, TLDR, Flickr wasn’t that big of a miss.

Interestingly, it was only a private company for one year before being acquired by Yahoo for about $25m. So, Accel maybe would’ve doubled their money in a year, which is a great standalone investment but a terrible venture capital investment (as we know the goal of VC investments is the return the fund on each investment), so it’s not a big deal that they missed this one.

They reportedly missed it for reasons very similar to Skype: young founders taking on an industry that could succumb to copyright issues.

What’s interesting about this deal, however, and as readers of the a16z essay know, is that Stewert Butterfield, the founder of Flickr, went on to found Tiny Speck, which would later pivot into Slack.

So, this is an example of how to handle an investment you passed on. The old “not now but keep us in the loop.”

I’m assuming the relationship between Butterfield and the Accel team must have been amicable despite passing on Flickr because Accel was one of the first investors in Tiny Speck back when it was just an idea.

Entrepreneurs tend to start more than one company, so it’s vital that a venture capitalist maintains strong relationships with as many as he or she possibly can because it’s very likely that person will be starting a new company in the future, and you want to be one of their first emails when they’re raising money.

Luckily for Accel, they kept that relationship with Butterfiled and were rewarded with about $5,750,000,000 worth of Slack shares.

Passing on Flickr but investing in Slack? I’m sure many investors would be happy with that outcome.

Conclusion:

I hope you learned the many lessons we discussed here today, but if I could sum them up into a few bullet points, it would be:

Look towards the future into pockets no one is investigating.

Let the founders lead the way.

Build and maintain relationships with any founder you meet, no matter how difficult they may be to work with initially.

These three principles have generated well over $25,000,000,000 in returns for Accel throughout their storied history. One could expect Accel to continue to return such massive amounts of money as they invest at the forefront of an AI-dominated world.

Stay tuned next week when we go a little deeper on how they analyze companies and founders when I elaborate on five questions I’d ask founders if I were a partner at Accel.

That is all for today; if you liked this essay, subscribe, and please share it with a few friends you think would be interested! I’m sure they’d be grateful you sent it to them. Also, if you want to listen to the podcast episode, you can do that here: Spotify or Apple. If you want to watch clips from the podcast episode you can check out the YouTube page. Lastly, you can follow me on Twitter, @Justin_Pryor_ for random tweets regarding the companies I cover and the lessons I learn.

Thanks again for reading and have a great rest of your day!