Why Construction-Oriented AI Robotics Are One of the Best Use Cases for AI

Why an autonomous bridge decay identification and repair robot is a fantastic startup opportunity.

Intro:

Last week, I talked about how an investor would analyze a startup building something completely new with high technical risk and low market risk. That company was Loyal, which makes dog life-longevity drugs. From a market perspective, it is one of the most no-brainer investments if they can pull off the tech, which obviously is a huge challenge.

It got me thinking: what are some potential startups where a company can create something new that may be very technically challenging but with minimal risk from a market standpoint that makes a current process either much better or much cheaper?

I closed the essay by saying I’m not sure Figure AI qualifies as a low-market risk company since many other startups and large companies are going after humanoid robots. I do, however, think intelligent robots will be highly prevalent in our world in the coming decades, so I thought about where intelligent robots could best be applied to enhance our world while being financially worthwhile for an investor.

For some reason, perhaps due to my Pittsburgh upbringing or the fact that I just read (and loved) Last Train to Paradise, my mind went right to automated bridge inspection and repair robots. Exciting right?!

I’ll get more into why I chose bridges later. For context, the government currently spends nearly $3b every two years on bridge inspection, despite the push for annual or semi-annual inspections, so there’s a need for greater efficiency there. Additionally, the government spends almost $15 billion a year on bridge repair, while estimates say there is currently about $125 billion in bridge repair spending needed to repair all of America’s bridges currently in poor condition.

So there’s certainly a market, and the current solution, human labor, is not getting the job done.

Perfect equation for disruption!

Companies like the Pittsburgh-based and YC-backed Gecko Robotics are addressing the identification problem today. They have little robots that scan around an entire oil tanker, building, or aircraft carrier to identify signs of significant corrosion that need to be addressed.

Now, that’s great, but I think developments in AI should allow companies to go one step further.

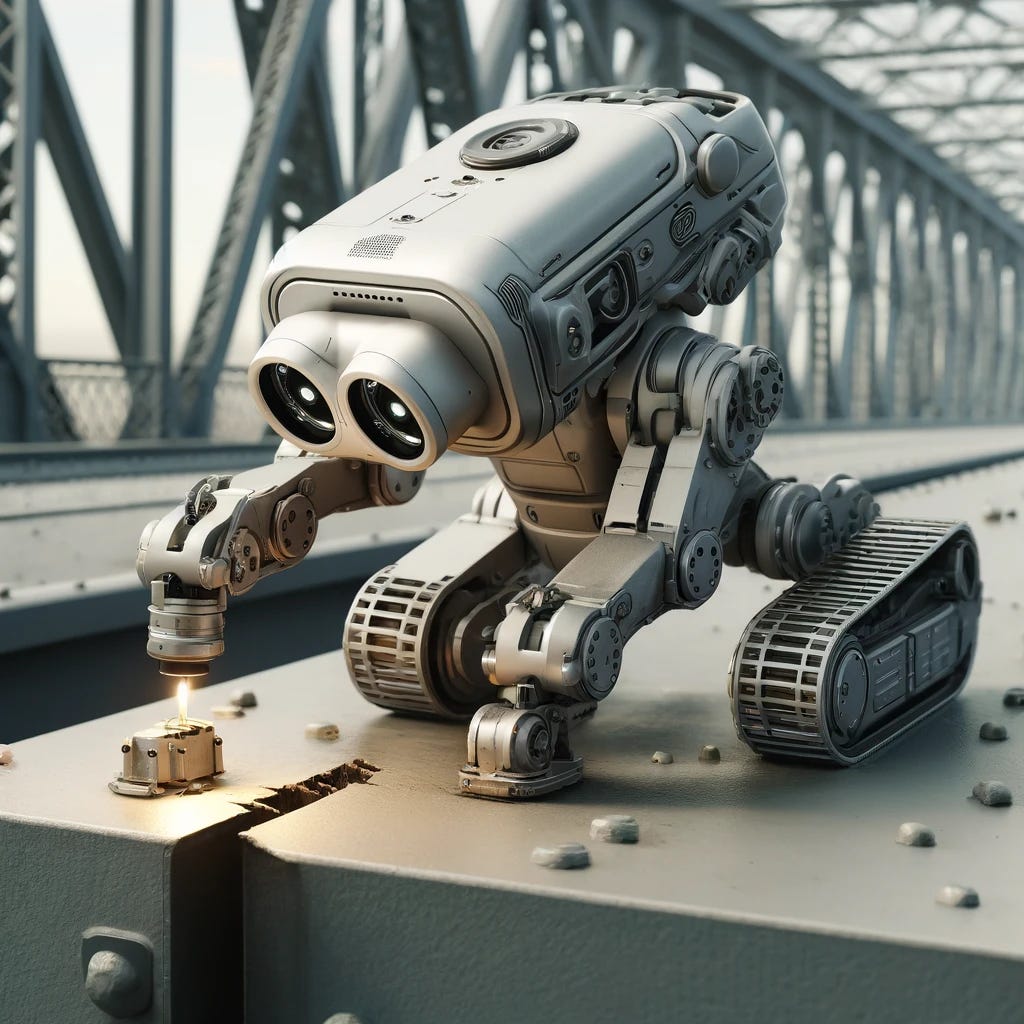

Go from identification to solving the entire problem because currently, Gecko will inspect a plant, and if there’s an issue, they tell the company to send some construction workers there to fix it. That’s great, and it eliminates the need for a human to risk their life to scale and meticulously analyze a building, but that’s only a smidge of the job. I’m talking about replacing the whole thing.

The concept I’m explaining is similar to what Benchmark Partner Sarah Tavel said when she posted a blog about how AI startups should “Sell work, not software.” Companies like Gecko Robotics are essentially building software in the physical world to enhance worker productivity—making it easier for them to analyze buildings. A software equivalent may be companies saying they’re the “co-pilot for lawyers” to speed up their work. Many of these companies say it improves worker productivity by 30% or so. What I’m talking about here with this next wave of companies are the ones that fully replace the lawyers.

As it relates to the physical world, I’m talking about companies that create robots that don’t just inspect the physical object but repair the object as well. Sell the work. Construction AI seems to be one of the best applications for selling the work, and bridge repair is a good place to start.

What will the robot look like? Well, there is Gecko Robotics, which is working on identifying corrosion and decay on things like naval ships and oil tanks, and MX3D Robotics, which can 3D print small pedestrian bridges. The startup I’m proposing, let’s call it BIRAR (bridge inspection and repair AI robotics), would combine these two concepts. Think of a Gecko Robotics build that can scale bridges on top, on its side, or upside down, with a retractable arm it can release that can weld certain pieces together like an MX3D Robotics, maybe even with some supplies and materials it can take out of a storage unit attached to it.

Is that easy to build? I have no idea, but probably not!

Can someone build it? Probably eventually!

Is it worth building if you can? Definitely!

So Why Bridges?

Replicable

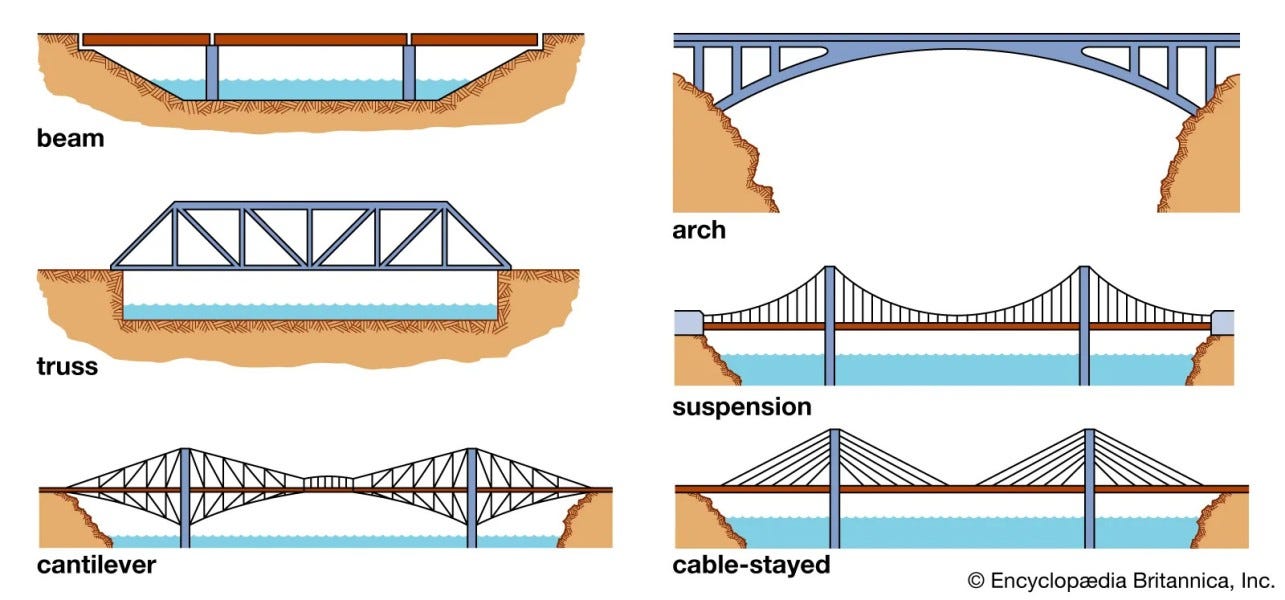

Bridges are very repeatable. There are a few variations of bridges when compared to the fact that there are about 600,000 bridges total in the U.S., so you can assume there are many thousands of each type of bridge.

Therefore, this AI model can start purely from learning data regarding truss bridges for its identification and repair practices. That’s a good way to apply seed-round money to get a product in the market since developing something like this will probably be very expensive. Then, you can expand training the model to more types of bridges one by one. I also suspect there are many replicable concepts regarding inspection and repair across all types of bridges, so there shouldn’t be too much additional training needed for these AI models.

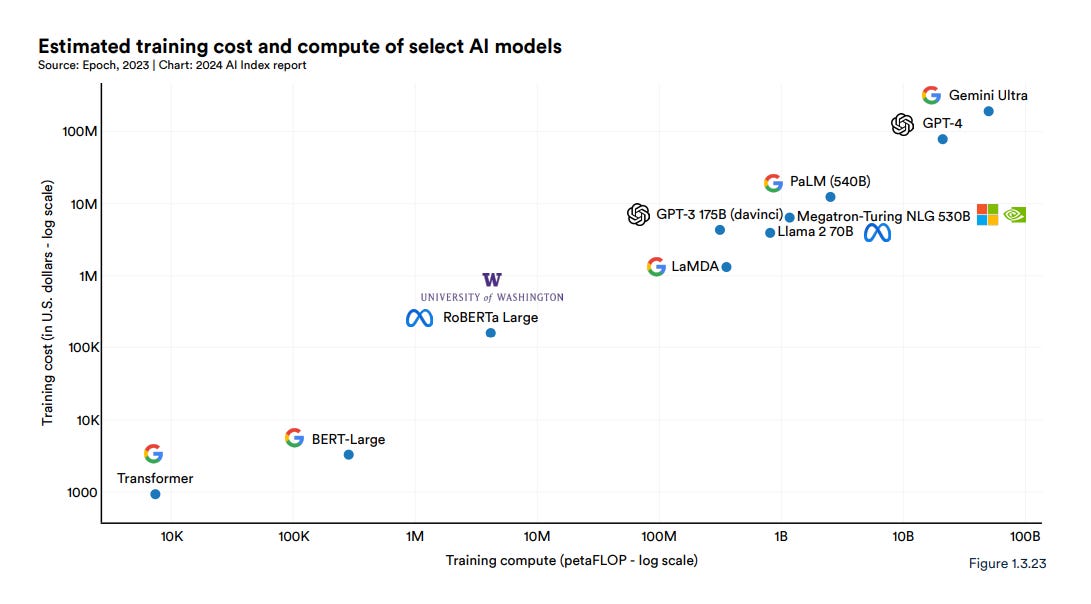

This is good because training an AI model is expensive.

At the same time, the cost to train AI models is rapidly decreasing, which is great, but any startup isn’t going to have a training budget like the companies on this list, as shown on the y-axis. By being highly targeted in the data you train your model on, you can do it cheaper and faster while becoming the smartest entity in the world on bridge inspection and repair best practices.

This is by no means the defensible aspect of BIRAR; that will be in the hardware, but it gets easier to build the hardware if you’re making the best possible software.

Federal Projects Rather than Commerical

The vast majority of bridges are funded with government money, and all of their information is public. Therefore, BIRAR wouldn’t have to pay anyone for proprietary information to train their AI models. It’s likely that some data will need to be licensed by certain construction companies for best practices regarding safety and efficiency in building, but I’m sure each county has its own best practices manual and extensive data repositories, so purchasing proprietary information may not be necessary.

As I said, most bridges are federal projects, so BIRAR would only have to sell to that county for contracts to repair all of its bridges. It’s challenging in the sense that government buyers tend to have many restrictions and long processes, but once you’re approved by one county, it should be much easier to roll out in the rest of the counties in that state.

There are about 1,200 bridges in Allegheny County, PA alone, so even landing one contract with one county is a multi-million ARR customer with very high lock-in and LTV.

The government can be the worst and best customer. The worst because there’s only one U.S. government, and it takes them a very long time to make decisions, but the best because once you have them, you have them for a longggg time. BIRAR mitigates the negatives because they won’t sell to the National Government but county-by-county, meaning they can make incremental progress starting with smaller, tech-friendly counties and working their way up.

If BIRAR were targeting commercial entities, like office buildings, it would have to sell to many different companies with many different best practices and train their models on each proprietary data set, and they may be restricted from intermingling that proprietary data with other construction companies. Also, private contractors are the competition since they use human labor at a higher price than what BIRAR would offer to the government, so they probably wouldn’t want to work with BIRAR unless they had to.

BIRAR is in and of itself a private contractor competing with today’s slow and expensive construction companies. Construction companies aren’t going to disrupt themselves by working with BIRAR because that changes their entire business, such as Google adopting LLMs instead of traditional search. It may be where the world is going, but Google will try very hard not to disrupt itself to get there. I suspect construction companies will face a similar dilemma in the construction robotics era since buildings will be much cheaper to build.

Competition is for Losers

I’ve mentioned this Peter Thiel mantra a few times in this blog, and I’ll continue to do so because I think it’s the core foundation of startups: creating something completely new to solve a customer's problem.

BIRAR will have a monopoly in this market by building the first pure-play “sell the work” solution to bridge inspection and repair, which is currently expensive, inefficient, dangerous, necessary, and has a major backlog with billions of dollars just waiting to be spent.

No one else is building this, so if BIRAR is first to market with a product that’s better, faster, and cheaper than the incumbent, construction workers, then they’ll build all the relationships with local and state government decision-makers to win large contracts to repair all bridges in a town, city, or county and keep expanding from there.

Also, this isn’t easy to build, obviously, so it’s not like a competitor will just pop up when they see BIRAR working. It’s not software. BIRAR will have solved a very difficult problem with a lot of proprietary information about how they did it locked in a safe. Thus, why has no one built something like this before? It’s really hard.

Thus why BIRAR will have no competition.

Bridges Inspection:

“The FHWA requires evaluation of all bridges however, it is costly having a biannual inspection cost of $2.7 billion for the U.S. where the average inspection cost per bridge ranges from $4,500-$10,000. This requires closing lanes for the span of the inspection, which can take 1 to 3 days, causing traffic congestion. With the rapid growth of highway transportation and the dispersed age distributions of bridges, fatigue damage is quickly becoming a serious concern. Therefore, the demand to inspect bridges before the 2-year period is rapidly increasing as the condition of these bridges deteriorates. To assure safety and prevent any hazardous damage of collapsing bridges as has previously occurred, the inspection period for these structurally deficient bridges ranges from 6 months to a year” https://catsr.vse.gmu.edu/SYST490/490_2014_BI/BIS_FinalReport.pdf

This report says the U.S. spends $2.7b every two years on bridge inspection but suggests they should inspect bridges yearly due to safety concerns. Enter BIRAR. If they can double the output by being more efficient, the U.S. can continue spending $2.7b every two years on work that will now be completed yearly.

As I said earlier, getting to inspection shouldn’t be very challenging, and that’s only the first piece of the puzzle. Inspection gets BIRAR in the door, building relationships with key decision-makers and teaching their AI models with real-time data so they can focus on the next phase because a $2.7b market is way too small for a startup.

The way I think about it is that BIRAR should focus all of its attention on being like Gecko Robotics: build the best bridge decay identification robot possible, going from one type of bridge to another, and then, once those robots are proficient and humming off of the production line right onto bridges generating a profitable businesses line for BIRAR, invest all of those profits, along with raising capital from investors after proving their initial milestones, to begin research into the repair phase.

BIRBAR’s path is to become THE bridge inspection AND repair company. Inspection isn’t the goal but merely the first step. You could compare it to Tesla building the Roadster as the proof of concept and a product that can generate some revenue to go mass market with electric vehicles, as they did. In this metaphor, bridge repair would be like the Model 3, a mass-market solution to a mass-market problem.

Bridge Repair:

Repair is the crucial piece of this puzzle. I don’t think BIRAR will have too much of a problem achieving the inspection phase. With the right team and enough capital, it can be done, as Gecko Robotics has shown. The hard part, and where this becomes a high technical-risk-low-market-risk investment, is in the repair phase because this has never been done at scale.

Contrary to bridge inspection, this market is large enough to be a standalone venture-backed business.

“There are more than 617,000 bridges across the United States. Currently, 42% of all bridges are at least 50 years old, and 46,154, or 7.5% of the nation’s bridges, are considered structurally deficient, meaning they are in “poor” condition. Unfortunately, 178 million trips are taken across these structurally deficient bridges every day. A recent estimate for the nation’s backlog of bridge repair needs is $125 billion. We need to increase spending on bridge rehabilitation from $14.4 billion annually to $22.7 billion annually, or by 58%, if we are to improve the condition. At the current rate of investment, it will take until 2071 to make all of the repairs that are currently necessary, and the additional deterioration over the next 50 years will become overwhelming. ” https://infrastructurereportcard.org/cat-item/bridges-infrastructure/

$14.4 billion a year is still a relatively small market, but it’s an underserved market that a startup can thrive in. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want the government to spend more money. Spending is already so out of control. I think the goal should be to keep spending at $14.4 billion but double its output so that the new production output via these robots is $28.8 billion worth of value—about 50% more than the suggested increase in this report.

Now, there are more factors that go into bridge repair than just a robot doing some welding. Certain testing, like load testing, can’t be done by these robots because it tests how the bridge responds to very large loads. That obviously requires a lot of weight. Some of this money may also be used to purchase materials needed for repairs, but I don’t think it would be too much. Frankly, I think most of these costs go to contractors, engineers, lawyers, and other consultants, with forms just being passed around and a few people actually repairing the bridge.

Again, all of this depends on the technical feasibility, which is outside my scope to comment on, but we know robots can inspect and repair/build bridges. The question remains: Can we combine those processes with an additional dose of autonomy and intelligence that makes it possible at scale? I think so.

As I mentioned earlier, like Loyal, BIRAR would be a company with high technical risk and low market risk. I don’t think the market risk is as low as Loyal since it’s easier to sell a longevity drug to crazy dog owners than to sell anything to the government, but there is no competition currently, and if you do land that customer, the government, you’re locked in for a very long time. So perhaps the market risk isn’t zero like Loyal, but it’s very low.

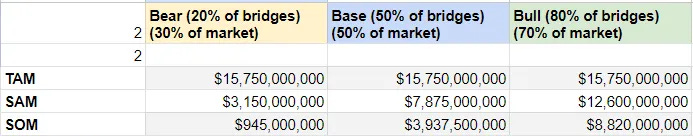

The TAM:

I won’t lie; while I think this is a promising idea for a brilliant team to go after, it’s not a super-promising venture investment. For this to be worthwhile, BIRAR would have to have confidence that they can inspect and repair at least 7% of all bridges in America yearly, which would get them to about $1 billion in ARR. BIRAR won’t be a $100 billion company solely by inspecting and repairing bridges in America (more on this later), but it certainly can be a $10 billion company if it gets contracts to inspect and repair maybe 15% of all bridges in the U.S. ($2 billion ARR with a five p/s ratio). That obviously sounds like A LOT of lobbying, which isn’t easy, and production capabilities, which will require a lot of upfront capital, but once relationships are built and production lines are humming, it should be a smooth operation.

Also, I know that projecting 15% of all bridges in America to be repaired by one company is crazy, but from a competitive standpoint, it can be done. As I said, current processes are slow and expensive. If BIRAR can satisfy that underappreciated demand, they should grow really fast, again, without competition.

There’s one big positive or negative aspect of this market, depending on your interpretation, which is that it is, and likely will be, stagnant for a long time. No boom in technology will increase the bridge repair market, nor will there be much of an increase in bridges built in the U.S. Some data suggests there are about 8,000 bridges built on average per year, but there are over 600,000 bridges currently, so that’s only a 1.33% growth rate. Pitiful.

The positive spin on that market is that it will probably be around still after we’re all dead. I don’t think we’ll be a purely air-based society in this century, a.k.a. flying cars, because just what a logistical mess that would be, but the point is if the inspection and repair market is $15.75b, it’ll be a very long time before it’s less than $15.75b. On the other hand, the smartphone market is hundreds of billions of dollars today, but in 25 years, it could very well be zero if we all get a Neuralink chip in our brain or AR contact lenses instead.

So, the market is very slow, but it’s very dependable—maybe not the typical venture market, but nonetheless a good market. However, there are a few market expansion opportunities that would take BIRAR beyond the U.S. bridge inspection and repair markets.

Now, you may be thinking about alllll the risks facing a business like this, which certainly exists, but before I get into all of them, I’m going to talk about a few market expansion opportunities for BIRAR to go beyond that kinda small and worrisome $15.75b TAM.

Market Expansion Opportunities:

Go Global

This is the most obvious one. If BIRAR can prove its technology works and no international company is competitive, then BIRAR should be able to expand overseas. However, they’d have to wait until they excel in the U.S. because they’ll have to train new robots on almost completely different training sets. Every country has different regulations, best practices, and languages for bridge inspection and repair, so training new models will be very expensive and time-consuming. BIRAR will likely raise money or generate some pre-sales if operations are sustainable to ensure it’s worth the massive R&D investment.

It’s very hard to predict a reasonable market. I think only a few countries spend $1b+ on this type of work per year, and probably the biggest market, China, won’t adopt U.S. technology, so maybe the global TAM is something like ~$40b. If so, that could be a large enough market for a $100b company if BIRAR produces attractive profit margins.

Nailing domestic production will be hard enough, but if BIRAR is successful in the U.S. inspecting and repairing bridges, I don’t see why they’d have an issue expanding globally, so this is a promising sign for an investor.

Build Bridges:

Perhaps if BIRAR knows how to repair bridges, they’ll learn how to build them. Maybe, but I don’t think that’s actually a very good business to go in. First, bridges rarely get built. In fact, there are way more bridges needing repair than need to be built, so it is a less attractive market. Second, it’s probably ridiculously hard to program robots to do the entire process from nothing to a full-scale bridge. Filling a few cracks and adding some additional layers is much easier.

There’s a market here, and I’m sure eventually, everything will be built by robots, but I don’t think we’re close enough to that for BIRAR to pursue. Starting with domestic repair and then expanding internationally seems like the optimal strategy.

Roads:

The estimated annual spending to maintain and repair roads in the U.S. is about $230 billion. Now that’s a massive market. You may be wondering why I’m not just proposing road repair robots rather than bridge repair robots.

Honestly, I didn’t think too much about it. I just felt that getting governments to support bridge inspection and repair robots would be much easier than roads. I think it’s easy just to turn on a few robots to scan a bridge and repair any issues rather than the massive coordination and material allocation required to repair roads.

V1 of BIRAR robots will probably be a scanner with a welding arm to fix cracks. That’s useful for bridges but not for repaving roads, so I felt getting a V1 would be hard. Road repair seems to have many more things you’d have to optimize for than bridges, so I felt bridges would be a better place to start. However, once BIRBAR can repair structures, they may begin to repair roads on those bridges if necessary, training their robots for that next stage if they see it as a promising opportunity.

Risks:

High Enough Margins?

According to ChatGPT, most high-end industrial automation and robotics firms have a 40-60% gross margin. That’s not great, and it’s not typical of a venture capital investment since software and even biotech companies tend to have 80%+ gross margins. That high gross margin tells investors that these businesses can spit out tremendous cash flow after a lot of R&D and marketing investment.

Now, I do think BIRAR would have decent gross margins. It’s actually more of a software company than a hardware company (though it would initially be very expensive software). They have to build robots, which will likely be very expensive, but they’ll be replicable and, ideally, have a long life so they can be used many times on many bridges.

BIRAR will never have as high gross margins as software businesses. However, there’s a defensibility around these lower-margin companies where the R&D is so difficult and expensive that it’s not easy to compete. According to Jeffries, SpaceX may only be about a 40% gross margin business. Still, it’s one of, if not the most defensible business in the world right now because it’s such a difficult engineering problem that no one can replicate it. No one will think it’s worthwhile to compete against SpaceX (though, I guess Blue Origin is making a run) since that’s an unappealing margin for a competitor to go after the scraps for.

Low gross margins contribute to this investment's high-technical risk, low-market risk thesis because the market is not attractive for many, and it will be even less attractive for the second or third player.

So, the low margins are a risk, but once the robots are built and operations are running smoothly, it should be a cash flow-accretive business since so many tasks are automated. The robots will only get cheaper as the cost of computing decreases, whereas construction worker salaries will only increase, so their margin will look increasingly attractive while their value proposition to governments matches that same attractiveness.

Upfront capital

I don’t think this will be a big risk if BIRAR takes a milestone-based approach, as all hard-tech companies should do. The goal is to raise a seed round on a concept with some evidence that the science and engineering around this product is possible and is designed by an exceptional team. With that $3-$4m, that team should be able to build a working prototype to fund the buildout of their robots through pre-sales to customers.

If more testing needs to be done on the prototype, or if, for BIRAR, more capital is necessary to train the robot, but the robot can at least conduct the tasks you set out for it to do in the initial fundraise, then BIRAR could likely raise a Series A based on that.

Since these hard technical problems are so defensible, investors are willing to invest in these companies based on slight progress rather than customer data. Sure, it may not be until a Series A or Series B that this company can sell its services, but if it continues to prove the product little by little, it should have no problem raising enough capital or funding development through pre-sales to get to the revenue-generating point.

Job Disruption / An Old Industry with a Way of Doing Things

This may have been a thought that crept into your head at the beginning of this post. Well, after doing some fairly minimal research, I found that probably no construction jobs would be lost if BIRAR worked on every single bridge in America.

This chart suggests that to meet construction demand, about 14.5% more workers are needed—from 8.3m to 9.5m. Also, 20% of construction workers are over 55 years old (nearing retirement age), and fewer young people are entering the industry. Therefore, once BIRAR starts rolling out its products, there won’t be any job disruption for a while as it will take a long time for BIRAR to become mass-market.

In fact, bridge inspection and repair is probably such a niche market in construction that even if BIRAR is working on every bridge in America, I’m sure there won’t be any job loss in construction if there’s about $2T in construction spend per year and bridge inspection and repair is only $15.75b per year. That’s barely a dent. Those jobs won’t be lost; they will just get reallocated to other construction jobs.

If anything, the next generation of construction workers may want to look for another path. I bet when they’re 55, there won’t be any construction jobs (robots will do it all), but that’s ample time to proactively find another career path. No one will be surprised by job loss.

Therefore, I’d consider job loss a non-factor in this process. A bigger concern is that this is just an old industry with old structures and principles. Many people may not want to use robots becasue they don’t trust them, or that’s just not how they do things. On the other hand, these are federal infrastructure projects, so it’s not up to the construction companies; it’s up to the government.

If BIRAR is the cheapest and most efficient construction company for bridge inspection and repair, then the government has to choose them, or citizens will not be happy. There’s concern that despite the data I just showed, governments will be concerned about job loss and not want to support BIRAR. Hopefully, they can interpret simple data, such as this chart above, and act in the best interest of the taxpayer to provide cheaper solutions to enhance the safety of our nation’s bridges.

Why I Wrote This:

While there aren’t too many of you out there reading, I’m hoping that this may be a call to action for at least one of you. I think really hard problems like these need to be solved, which is what our best and brightest should work on. This project benefits every single human, both financially and mentally (alleviated safety concerns), so it’s one of the most virtuous projects you can undertake.

Yes, this is a call to action, but it’s also a personal exploration of what industries I find most interesting as a hopeful venture capitalist. Startup investing is so crowded with so many different theses that it’s hard to understand where the most alpha currently is in terms of which companies being built now will be multi-billion dollar companies in 15 years.

Within the next few essays, I’ll explain why I think investing in market-defining companies that either create a market by building something completely new or drastically expand a market through an innovation is the optimal path. Most of the time, these companies will have high technical risk and low market risk, though not always. A good way to think about it is, will this be something you’ll have to “sell,” or will customers break your door down for it? I’m more interested in the latter.

I hope you enjoyed this essay/episode and felt a little more inspired to explore the feasibility of some moonshot ideas. We’re in the early stages of a major platform change through the acceleration of AI and LLMs, so those moonshots won’t seem too crazy a few years from now.

Those who take the leap first will get rewarded the most.